Chiropractic

The article below appeared in the Australian July 2nd 2011.

THE scene inside Warren Sipser's chiropractic consulting room on a weekday morning resembles a kindergarten more than a health centre.

Kids tumble around the floor of the reception area and its adjacent open-plan treatment room as young mothers congregate near the reception desk, where racks of naturopathic products and vitamin supplements are arrayed against the wall. On this Thursday morning, Sipser is at work adjusting the spine of Maive Dowling, a six-week-old baby, pressing her back with a chrome steel chiropractic "adjuster" that resembles a giant hypodermic syringe.

"It's her fourth adjustment so I know her patterns," Sipser says, as he feels along the infant's spine with his hands. Baby Maive doesn't have a back problem - she has reflux, which Sipser says he can alleviate by manipulating her spine. It's a belief keenly endorsed by the baby's 34-year-old mother, Amy Dowling, who has been bringing her three children to this chiropractic clinic in the inner-Melbourne suburb of Elwood almost weekly for several years. "When my son Ned was only a couple of days old, Warren came to the hospital just to check him over," she explains.

Sipser calls himself a "primary care provider" and refers to his practice as a "wellness centre". This keen-eyed 34-year-old rattles off medical terminology, assuring parents that all manner of children's health problems - colds, ear infections, colic, bed-wetting, hyperactivity, asthma - may be caused by spinal misalignments. It's a passionate belief he buttresses by producing a raft of journal articles that suggest chiropractors can repair DNA, optimise the immune system and make vaccination unnecessary.

Warren Sipser at his "wellness centre" with six-week-old patient Maive.

"It's about whole health," says Sipser, who originally trained as a paramedic in South Africa but graduated as a chiropractor from RMIT University in Melbourne 11 years ago. "Things like ear infections, colic and asthma are the most common issues, but taking a proactive approach means you can see kids on an ongoing basis for body balance and even DNA repair." Children now make up 40 per cent of his business, says Sipser, who is completing a masters degree in paediatric chiropractic at RMIT.

Chiropractors have long ranked as the most popular alternative-health practitioners - there are more than 4000 of them across Australia. Their mainstay treatment is an "adjustment" of the vertebrae to realign the spine. But Sipser symbolises a relatively new phenomenon: the chiropractor as family physician. Spurred by the public's hunger for alternative healthcare, practitioners such as Sipser are venturing far beyond the simple relief of back pain.

Not surprisingly, it's a development unwelcomed by many sub doctors. With the Federal Government launching a new system of policing the burgeoning "complementary medicine" industry, leading Australian scientists and doctors have come out with guns blazing against chiropractic teaching and practice. At the heart of their campaign are questions that affect the whole field of alternative healthcare: How do governments protect the public, particularly children, from quasi-medical services? Who regulates the claims made by such services? Are universities legitimising scientifically questionable ideas by offering Chinese medicine, naturopathy and sundry other unconventional courses?

Among those who have stepped into the fray are vaccine expert Ian Frazer, immunologist John Dwyer and paediatrician Jenny Couper, all of whom have raised objections to the chiropractic care of children. If this backlash has a central command, however, it's to be found in the living room of a house on a 19ha block in semi-rural Queensland - the home of the Jellybean Lady.

"Like most people, I thought that chiropractors just do backs," she says, sitting on the balcony of her Queenslander. "When I saw they were treating children I was absolutely horrified. One of my girlfriends told me that her baby was picked up by the neck. That was it for me. I thought: What are they doing with babies?"

Marron was shocked that RMIT University in Melbourne - one of only three universities in Australia authorised to train registered chiropractors - operated a suburban clinic that treated children. In March she enlisted 11 scientists, including Ian Frazer and John Dwyer, to put their names to a letter demanding that the Gillard Government close the clinic. The university says its clinic only treats children for musculoskeletal conditions, adding that its course "meets current professional standards". But the brouhaha highlights the controversies that await university science faculties which embrace alternative health. Even some chiropractors are scathing about RMIT, which runs the most established chiropractic course in the country and enrols nearly 200 students a year.

John Reggars, vice president of the Chiropractic and Osteopathic College of Australasia, published a paper in May accusing the university of teaching "pseudo-science" to its students. Reggars believes RMIT is reforming its chiropractic teaching as a result of the controversy. RMIT's head of chiropractic, Tom Molyneux, said in a prepared statement that the university was reviewing the course as "part of a wider initiative within RMIT's School of Health Sciences". But Molyneux refused to respond to the criticisms voiced by Reggars, Dwyer and others.

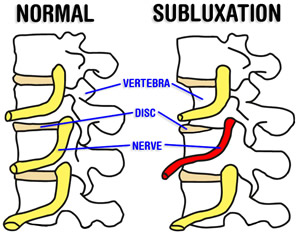

Chiropractors have long been split into two factions. Practitioners such as Reggars focus on back and neck pain, but a fundamentalist camp follows the teachings of the profession's founder, D. D. Palmer, a 19th-century magnetic healer in the US who believed that spinal adjustments unlock the body's God-given energy flows. The fundamentalists argue that each vertebra in the spine influences corresponding internal organs, and that chiropractors can heal the body by correcting minor spinal lesions known as "subluxations" which affect nerve-flows. This theory has been repudiated by many leading chiropractors in the 120 years since Palmer proposed it; last year, Britain's General Chiropractic Council reiterated that it is a purely theoretical concept "not supported by any clinical research evidence".

When governments introduced registration of chiropractors across Australia in the late '70s, their intention was to boost the scientific rigour of the profession. Chiropractors could only be registered after completing a five-year university course incorporating biological and physical sciences, and practitioners such as Reggars nursed a hope that the profession would take its place alongside physiotherapy and osteopathy as a first-line treatment for back and neck pain.

But the exploding market for complementary medicine has encouraged many chiropractors to diversify, and in 2006 the Chiropractors' Association of Australia gave them its blessing by endorsing a plan to make chiropractors the country's "most effective and cost-efficient health regime of first choice". The association lists the subluxation theory among its "core beliefs" and aims to ensure that university courses teach it.

Reggars argues that RMIT, which once had a scientifically rigorous course, adopted this agenda. He says that during his tenure on the registration board he heard many complaints from the public which made it clear that some university-trained chiropractors were operating outside their area of expertise. "There was an overt push to talk about chiropractic being a total alternative healthcare system and promote this idea that spinal issues have the ability to influence the body's 'innate intelligence', which I believe is nonsense," he says.

The family practice

The "wellness" message now promoted by many chiropractors has struck a chord with educated parents who increasingly question western medicine's reliance on drugs and technology. At Warren Sipser's practice in Elwood, the mothers speak of their understandable concern to protect their children from the dangers of overprescribed drugs such as antibiotics, and their desire to find safer and more natural treatments for common ailments. They want the best for their children. Amy Dowling explains that she first started bringing her children here after Sipser cured her migraines and back pain without drugs. Before that, she says, doctors had insisted her spinal curvature was not the source of her migraines and prescribed her a drug which has unwelcome side-effects.

So when her infant son, Ned, got an ear infection and the family GP recommended antibiotics, she instead took him to Sipser, who performed a spinal manipulation and recommended garlic drops in his ears. "If you go to the doctor you just get antibiotics, you don't get information about what they do to you," she says. "Warren has these seminars on Wednesday night where you get a lot of information about drugs, lifestyle, diet and exercise."

It's a view echoed by another mother at the Sipser practice, Liz van der Slot, who hardly ever takes her two children to the GP anymore. "Everything they have had - coughs, colds, croup - I have come to Warren and they have got through it without any need for antibiotics," she says. "Filling in the medical forms at school, I often put Warren down as our doctor. He knows those children so well, how their little bodies work, that he would know more than any doctor who's seen them once or twice."

Van der Slot believes Sipser cured her 10-year-old daughter's asthma, which doctors had failed to clear up using steroidal drugs. "When Georgia was four she complained of a sore back and I took her to Warren and he did an EMG scan and right at the spot she had been pointing to, she had a black mark that indicated a severe subluxation. Warren also could see she had a very marked eczema and asthma pattern in her neck." By way of explanation she motions towards a chart on his wall that depicts a spine with coloured horizontal bars radiating out from each vertebra, indicating an ailment or condition linked to a particular spot on the spine.

The chart comes from a US company that makes a device called the Insight Subluxation Station, which Sipser uses to diagnose patients. It employs surface electromyography (EMG) to detect electrical impulses in muscles, along with information on heart-rate and temperature which is fed through a computer to produce a chiropractic diagnosis. "It measures how much activity is in the muscles, and the thermal reading measures activity in the autonomic nervous system," explains Sipser. "It shows how the nervous system is communicating with the organs."

Reggars believes this is absolute nonsense. "Surface electromyography as typically used by chiropractors is just a gimmick and sales tool to encourage people to have chiropractic care," he says. There is absolutely no evidence that surface EMG yields any information about internal organs, says Reggars, an opinion shared by Sydney University's co-ordinator of musculoskeletal physiotherapy, Andrew Leaver. "I don't know of any research that has even looked at the link between EMG results and organ pathology," says Leaver.

For a parent concerned about her child's health, however, watching the computer-screen's horizontal graph-lines turn from dangerous black to benign white is reassuringly scientific. "I do like it because it's something black and white, you can see the changes in the body," says Liz van der Slot, whose children receive an EMG every six months.

Sipser says EMG is just one of many diagnostic tools he employs, and he rarely uses it on children under 11. The Insight Subluxation Station, he points out, was passed by the Therapeutic Goods Administration. But the device is in a lowrisk category that includes ear-candles, which means the TGA does not independently verify whether it works before listing it. "A lot of these practitioners think these devices work," says Marron. "They care about people - if they were nurses, they'd be great. But they're getting ripped off, they're investing tens of thousands of dollars in a device they think will help their patients. The practitioners aren't my enemy. My enemy is the TGA for not regulating [the devices] properly."

Miracle cure?

One of the mothers who attends Warren Sipser's practice is convinced he cured her three-year-old son Noah of autism. At age two, says Elizabeth, Noah would not make eye contact or talk, and a paediatric team at Melbourne's Royal Children's Hospital diagnosed an autistic-spectrum disorder. But since Sipser began manipulating the boy's neck she says there has been a dramatic improvement and she has completely rejected the speech and learning therapy recommended by hospital physicians. "Can I prove it? Of course I can't," she says. "But I'm convinced that the subluxations were the cause of his developmental delays and the chiropractic treatment is the reason he has got better." Elizabeth remembers that unlike the doctors, Sipser confidently told her he could "fix everything".

A scientist would tell you that such anecdotal cases are meaningless and that there is not the slightest clinical evidence that chiropractors can treat autism. Sipser himself says he would never claim to cure autism and Elizabeth may be misremembering what he told her. Nevertheless, he says Noah has improved under his care.

How does science explain the testimony of parents who believe their children's ailments were cured by spinal manipulation? Professor Jenny Couper, head of paediatrics at Adelaide University, points to studies which show that up to 70 per cent of people who consult an "empathic practitioner" will report improvement even if their "treatment" was in fact a placebo. Conventional medicine struggles with the implications of such research, which suggests that what we often call illness is more to do with belief than pathology.

Time and again, the mothers who visit Sipser's clinic talk about his patience, his reassuring manner, his careful explanations of his treatments - the kind of empathic service that overburdened GPs find increasingly difficult to provide. "He is always able to explain exactly what's going on, and educate me at the same time," says Liz van der Slot. "I find that lovely, that someone will educate you rather than just offering you a script."

Reggars points out that many childhood ailments subside of their own accord. "The results these chiropractors get for non-musculoskeletal conditions are usually serendipitous and have nothing to do with spinal manipulation and more to do with the placebo effect or the natural history of the condition," he says.

Sipser rejects this argument, saying that patients wouldn't keep coming back if his treatments did not work. "These are intelligent people making intelligent, objective decisions," he says. "They wouldn't do anything, and I as a father wouldn't do anything for my own child, unless I believed it was safe, gentle and effective." Chiropractic care for children is increasingly supported by medical research, he says. By way of evidence he cites a range of articles published in chiropractic publications, in particular the Journal of Vertebral Subluxation. One heavily footnoted article from 2005, written by several chiropractors and a Swedish molecular biologist, suggests that chiropractic care may slow down ageing by improving DNA repair.

That article is now cited on the websites of scores of chiropractors around the world. But according to Professor Steven Salzberg, director of the Centre for Bioinformatics and Computational Biology at the University of Maryland, it contains a statistical error which renders it meaningless. "A decent journal would never have published a paper with such an elementary error," says Salzberg. "From their discussion, it doesn't sound like they really understand what DNA repair is in the first place."

It is ironic that complementary medicine is now using the language and technology of science to woo patients away from GPs. Among the articles Sipser distributes to his patients are pamphlets warning of the dangers of vaccination. Like a growing number of chiropractors who believe in the body's "innate intelligence", he argues that childhood immunisation is risky.

Asked whether chiropractors are qualified to give such advice, given their lack of medical qualifications, Sipser replies: "It isn't outside our role because our role is to provide information on healthcare. If there is a potential for something to harm someone, whatever that may be, I am well within my scope of practice to warn them." In the case of patients with serious conditions such as cancer, Sipser says he confers with their medical doctors.

Certainly some of his patients see few limits to what he can do. When Liz van der Slot's five-year-old son broke his thumb recently, she brought him to Sipser, who x-rayed it and set it in a splint. The entire family now visits the clinic every two weeks for a "wellness check".

The cost of such services has long been a source of controversy. In 2005, the Chiropractors Registration Board in Victoria suspended the licence of Mark Pearson-Gills, finding him guilty of unprofessional conduct for recommending that a mother pay $1200 up-front for 60 consultations to improve her newborn baby's breastfeeding. One of the chiropractors who gave evidence in defence of Pearson-Gills was Sipser, who told the board he thought the care-plan was "reasonable". Sipser says today that he believes Pearson-Gills deserved to be deregistered and that he offered his testimony in order to defend the right of children to consult chiropractors.

At his own practice he offers a special family package which involves blocks of consultations at $35 per visit. Liz van der Slot has private health insurance and estimates it costs her family only $10 a week. For those without insurance the burden is considerably heavier: Amy Dowling generally pays about $300 a month for her family's visits to the clinic.

Some chiropractic patients can now claim for their care under Medicare, a cost to the taxpayer that grew more than fivefold to $10 million from 2006 to 2010. That has not gone unnoticed in Canberra, where the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency was launched last year to police not just doctors and dentists but osteopaths, chiropractors and other alternative practitioners. A national Chiropractic Registration Board has been established, and Reggars believes the profession is now at a crossroads where it can either embrace evidence-based science or find itself marginalised alongside homeopathy and iridology.

Sipser says chiropractors such as Reggars are part of a tiny minority who deal only with neck and back problems and have little influence over the great bulk of practitioners. "That's a very small part of the profession and they sometimes get publicity because controversy sells newspapers and television shows," he says. "In truth, their numbers are so small that we can't gauge what effect they are having."

As for the parents who visit Sipser's wellness clinic, their testimony would surely make a doctor blanch. "The only time I go to the doctor now is to get a script for the EpiPen for my daughter's nut allergy," says Liz van der Slot. "They actually get almost cross with me these days. They say, 'You never come anymore.' I would have thought they'd be happy we don't need to go there."

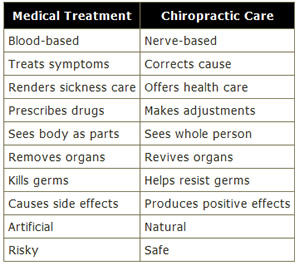

Chiropractic vs. Medicine

Traditional medical treatment relies on putting drugs into the bloodstream. Chiropractic care helps restore nervous system integrity by reducing subluxations. Two very different approaches:

The advertisement above was taken from the web site http://www.crainwellness.com/what-is-chiropractic/chiropractic-vs-medicine/

What is chiropractic treatment?

How did it evovle into a alternative medical treatment?

What ailments to some claim to be cured by chiropractic treatment?

What is a vaccine, how does it work and why is it given?

Are vaccines dangerous?

How would a chiropractic manipulation prevent a viral infection much like a vaccine does?

Is it right for taxpayer's money to be supporting chiropractic treatments and for that matter homeopathic treatments when there is no scientific evidence that these treatments work better than a placebo?

Consider the advert above medicine vs chiropractic. Argue against some of the assertions it makes of modern medicine when comparing it to chiropractic treatment.